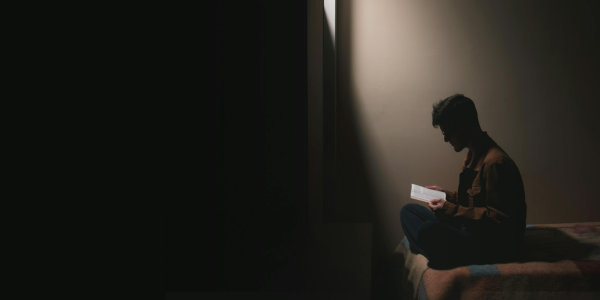

In Ray Bradbury’s nightmare vision of the future, Fahrenheit 451, the reading of books is prohibited. “Firemen” are summoned to offenders’ homes to burn their books because the authorities fear the ideas contained in them. Citizens are encouraged instead to watch mindless soap operas on giant telescreens. The salvation for such a society lies in its outcasts, eccentrics who live a twilight existence on the fringe of the society, and whose job it is to memorize entire books worth saving for the benefit of posterity. These ‘walking books’ value what they have committed to memory for the same reason that all thoughtful people do. We read for pleasure. We read for information, recreation, inspiration, and instruction. We read both to be lifted out of and to be taken deeply into ourselves. What we seek in reading, said C.S. Lewis, is “an enlargement of our being. We want to be more than ourselves.” If what we read is truly good, we make ourselves, ultimately, better people, increasing our understanding of the human condition, developing empathy for others, thereby improving the society we all share, and clarifying for ourselves our place in the fascinating but bewildering universe that is our inheritance. “The substance of my being,” wrote Allan Bloom in The Closing of the American Mind, “has been formed by the books I learned to care for. They accompany me every minute of every day of my life, making me see much more and be much more than I could have seen or been.” We become what we read.

This process begins early. My wife recalls being read in Grade 1 Aesop’s fable about a contest between the sun and the wind, each of whom tried to make a traveller on a lonely road take off his overcoat. The wind blew and the sun shone. Louise learned that light, warmth and radiance are more conducive to change than the sound and fury of the wind’s huffing, puffing, and howling, which only made the traveller draw his coat more tightly around himself. Children who are read to absorb such stories effortlessly, and when they can read for themselves, the process is accelerated. As a child myself, I could not be persuaded to eat cheese until I read, at the age of eight, Johanna Spyri’s lyrical descriptions of cheese-making in the Swiss Alps in her classic children’s novel Heidi. I have been grateful to her ever since.

The appetite for reading, then, is ideally acquired young. Michelle Landsberg, an authority on children’s fiction, has written that books were for her “more than an amusement” in her own childhood; they were “my other lives, and the visible existence I now lead in the workaday world was touched and transformed by them forever.” In his affecting memoir The Child That Books Built, Francis Spufford recalls being so moved as a child by the lion Aslan’s guardianship of the children in C.S. Lewis’ The Narnia Chronicles that he tenderly kissed a picture of Aslan on the nose. The writer Jane Gardam remembers how she, as a four-year-old, explained to her mother the meaning of the word ‘soporific’ in a Beatrix Potter story about rabbits. She had worked out its meaning from its context, proving that yet another benefit of reading is the unconscious acquisition of a growing vocabulary. The more we read widely and deeply, the more our powers of expression are developed: our own syntax and diction improve while we are beguiled by story. Good writers are inevitably—and necessarily—good readers.