I’m not sure why in ’85 I decided to start my tour of Ireland and Britain with a visit to my Aunt Muriel. She picked me up at the Belfast airport. I didn’t ask her to. I’d given her my flight information, but said I’d find my own way to Rathfriland. She’d been waiting for me for three hours and was in a mood when I arrived.

After a couple days together and after I think I’d convinced her I wasn’t there seeking an inheritance: “I don’t have much money, you know,” she’d announced a couple times. “Neither do I,” I’d replied, “So, I think we’re pretty much on even ground.” After all that, we became if not friends, friendly. We liked each other.

When Sunday rolled around, she asked if my dad still attended the Presbyterian Church. I said, “No. He’d never attended any church in Canada that I knew of.” “Oh,” Muriel said, “That’s a surprise, given the way he was raised.”

She asked if I was a “practicing Catholic?” I told her no, but that my mom did raise us five kids as Catholics. We’d walk with her to the 8:30 morning mass every Sunday – snow, sun or showers. My dad never joined us.”

I told her “Feminism was my new religion.” She laughed and asked if I wanted to attend the service at The First Rathfriland Presbyterian Church with her. I said “Sure.”

The First Rathfriland Presbyterian Church sat in town at the top of Newry St. – “A light on a hill,” was its ‘tagline’. You had to pass the Rathfriland Baptist Church, St. Mary’s Catholic Church, and the Second and Third Rathfriland Presbyterian Churches to get to it. For a town of about 2,400, it had a lot of churches.

When we entered, the elders all sat at the front facing the congregants. Samuel would have sat among them in his day. The pews had family names on them, and were ordered in some kind of hierarchy. The Greene’s pew was near the front, immediately behind the Gamble’s.

As soon as we settled in, the older woman in front of us turned and asked me, “Who would you be, then?”

I said, “I’m Carol Greene, Muriel’s niece from Canada.”

“Oh,” she said, “I knew your granddad, Samuel. He worked for us at the hardware store. Lovely man.” And then she turned again to face the front where the reverend climbed the steps to the raised pulpit wearing a red cloak with a large white fur-trimmed collar.

Muriel leaned over to whisper, “That’s Mrs. Gamble. The richest woman in Rathfriland and now suffering a little memory loss.”

The reverend commenced to deliver a fiery sermon, denouncing Catholics and their faith. Ridiculing transubstantiation – the belief that the eucharistic gifts actually change into the body and blood of Christ.

Then Mrs. Gamble turned around again.

“And who might you be?” she asked.

“I’m Carol, Harold Greene’s daughter,” I whispered to her.

“Oh, I knew your granddaddy! He worked for us in the store. Sure, he was a lovely man.”

The minister continued preaching hate, preaching division. This severe man elevated above the other severe-looking men all severely looking out at us. He raved and ranted about true consecration and how it was through their faith and their faith alone that it could be achieved.

Mrs. Gamble twisted her head again: “Who are you, then, dear?” she asked.

“That,” I replied, “is a very good question.”

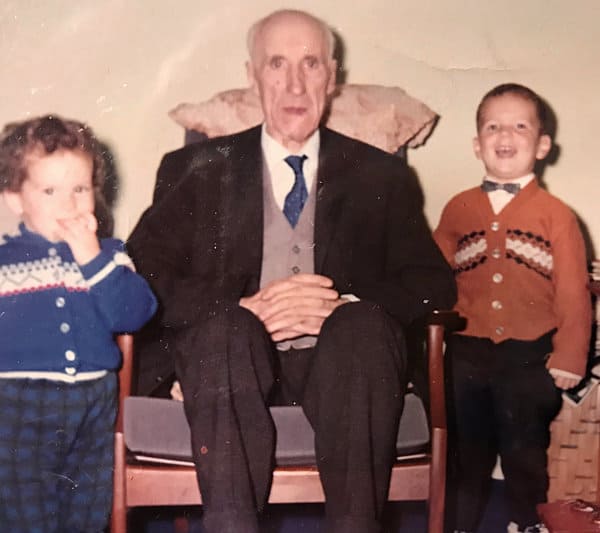

Carol, Samuel and John Greene, 1964