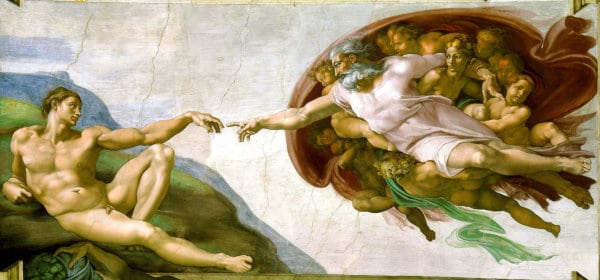

My colleague Gaël and I were standing amid the chattering mob in the Sistine Chapel, craning our necks upward like the others all around us. High above us the glory of Michelangelo’s ceiling swept from end to end. The frescos were undergoing restoration, so our view was somewhat concealed by the wide moveable platform that provided the workplace for the restorers. Of all the scenes that could have been concealed during our visit, the key fresco of God emerging from Heaven in a cloud of cherubs to touch the hand of Adam had to be the one. Nevertheless, seeing the rest of ceiling for the first time I was overwhelmed. As we stood among the crowd, a lady behind us was telling her young son that the colours were too bright; the restorers were not following Michelangelo’s original colours, but were repainting them. I had read of the group of art historians, led my an American academic, who were marshaling to protest the restoration, and remembered a television feature where the academic in question had held up a pre-restoration picture of the dark and muted ceiling, dulled by generations of candle smoke and external pollution. He compared this with the new, fresh surface that was being revealed – the luxurious pale greens and lilacs and pinks – and claimed that it “Jist looked roo-awng.” But the wrongness in my understanding was centred in a set of art historical values that clearly needed revision. I recalled a similar controversy over the cleaning of paintings by Titian, and had even heard a professor of art history in my student days describing muted browns and ochres long after they were revealed to be simply the yellowing and aging of varnishes. Titian’s skies were blue, although art historical theory said otherwise.

However, the claim from the lady behind us that the restorers were adding colour caused Gaël to bridle. He turned to her, and wagging a long finger, explained to her and her son in his gorgeous Breton-flavoured Italian that “Not one gram of pigment is going up that elevator to the platform! These are Michelangelo’s colours!” And here is where coincidence plays such a tactical role in our lives: one of the restorers was at that very moment passing through the crowd on the way to the elevator that ascended to the platform, and had overheard the pigment diatribe. There was a schedule of half-hour guest slots throughout the day, so that specialists from around the world could visit the restoration workplace. Appointments had to be booked many months in advance. The restorer approached us. “Are you waiting to go up?” he asked. “Magari!” shouted Gaël, which translates simply as ‘maybe,’ but actually meant ‘Would God so smile upon us!’ Apparently the guests for that time slot had not materialized, and the restorer had thought we were they. Well, after introductions where we described our conservation and restoration backgrounds, and explained that we were teaching a course at the International Centre, we were naturally invited to take the open half-hour time slot. So there we were, squeezed into the little elevator that whisked us far above the crowd.